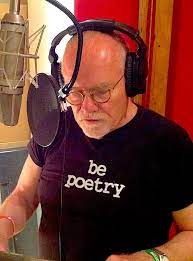

Charles Carr is an integral part of the Philadelphia Poetry Scene. His poetry has been published widely in the small press and three collections of his poetry have been published. He is the host of Philly Loves Poetry on Philly Cam and is active with the Moonstone Arts Center. A native Philadelphian, Carr attended LaSalle and Bryn Mawr Colleges, earning a Masters degree in American History. He has been an advocate for services for abused and neglected children for 35 years. More recently Charles has worked as a volunteer to promote the cause of the poorest of the poor in Haiti. Charles is married. He has one son

Charles Carr is an integral part of the Philadelphia Poetry Scene. His poetry has been published widely in the small press and three collections of his poetry have been published. He is the host of Philly Loves Poetry on Philly Cam and is active with the Moonstone Arts Center. A native Philadelphian, Carr attended LaSalle and Bryn Mawr Colleges, earning a Masters degree in American History. He has been an advocate for services for abused and neglected children for 35 years. More recently Charles has worked as a volunteer to promote the cause of the poorest of the poor in Haiti. Charles is married. He has one son

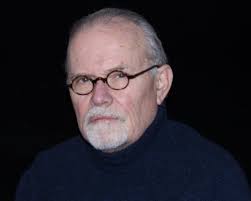

An interview with g emil reutter

GER: How did you come to poetry as an artform?

Actually, poetry came to me first as a form of meditation. I wrote my first poem twenty years ago. I had returned to Philadelphia and was staying with friends as I was looking for a new job. My ironing a shirt for a job interview prompted me to remember the pleasure of ironing, something I started to do when I was 12 and something my mother taught me. The poem was titled “The Revolution Has To Wait”. I made the task a reminiscence of my mother’s instructions on the exact order of the task, reflections on the agony of those young women (wayward they were called) in Ireland who enslaved in the famous Madelaine Laundries, ironing my altar boy cassock and surplus. I shared the poem with a close friend who is also a writer, he loved it and urged me to keep writing.

GER: You are the host of Philly Loves Poetry. How did this come about and how has the program developed over the years?

Moonstone for a brief period sponsored a PhillyCAM broadcast titled “Who Do You Love”. The program focused on the great poets – Neruda, Yeats, Rilke and others. The program hosted a panel of poets and others who discussed and offered their analysis of the poet’s work. This usually was followed a brief open mic where a select number from the audience would read poems of the “loved” poet for the night. Over time the program lost momentum and the panelist who were invited didn’t show up. Larry and I discussed the potential for a replacement. I recommended that we focus on local poets, and we came up with the title Philly Loves Poetry. At times the format has changed from “themed” programs (e, g Veterans, Ekphrastic, Whitman 200 celebration etc.) to what it is now: hosting a discussion and the guest poet reading a selection of their poems.

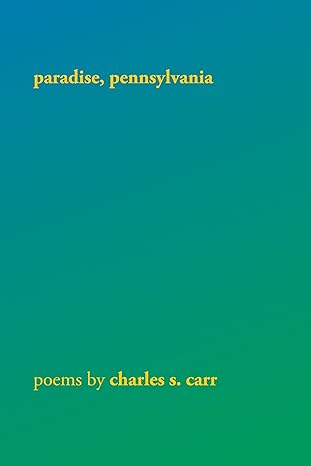

GER: Your first poetry book, paradise, Pennsylvania, was released by Cradle Press. How did the book come about?

Actually, the book came about accident and good fortune of meeting a publisher while vacationing with friends in Michigan. By 2008 I had gathered a collection of poems, which I wanted to submit to publishers. I met the publisher of Cradle Press who lived in St. Louis who also was a poet (and an international security consultant). I told her about my collection and asked if she would read it and give consideration to publishing. I sent her the manuscript. She liked it and we published. I lived and worked in Lancaster County for almost five years and had a lot of contact with the Amish and the signature poem is dedicated to them. The collection cuts across a wide assortment of things-including the resting place for old wallets, requiem for pens, to my 1984 Volvo.

GER: How has the Moonstone Arts Center impacted the Philadelphia area and beyond?

I know of no organization in this City and or other cities that has done more to advance love poetry and to use poetry as a platform to speak to the many issues we face as a City and a nation. My book “Haitian Mudpies” was the first book of poems published by Moonstone, (beyond the annual Poetry Ink Review Anthology). Since that that first book, published in 2013, Moonstone Arts has published over 200 books, which includes, large collection. Chapbooks, and topical Anthologies. Yearly Moonstone hosts 100 readings in their poetry series which has given approximately 300 poets a venue to read their poems. As I said often publicly Larry Robbin and Moonstone Arts Center are a cultural treasure of this City. There is no way to quantify or evaluate the impact that Larry and The Arts Venter have had on the cultural life of this City.

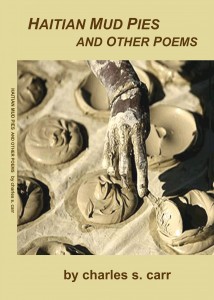

GER: Haitian Mudpies & Other poems is your second release. The title is unusual, creative to say the least. How did this project develop?

In 2005 a close friend of mine who had been making trips to Haiti for several years invited me to stay at the mission Hands Together and to volunteer for a week at an Infirmary and Orphanage run by thy the Sisters of Charity, the order founded by Mother Teresa. During our stay Father Tom Hagan, an Oblate priest, and former Philadelphian, took us for a tour of the schools his mission built in Cite Soliel, a slum in the capitol City of Port-au-Prince. During unforgettable tour Father Tom accompanied up a set of stairs, where a watched a woman sitting in the blistering sun, forming small patties. I thought these patties were hand pieces of pottery, which she would paint. Father Tom told me she was making “mudpies”, which she will sell at the market and which the starving people of Cite Soliel eat! This experience combined with the volunteer work in the Infirmary feeding and comforting was life changing. I did make a few more missions to Haiti until the Earthquake in 2010. After this I agreed to become a lay missionary for Hands Together traveling to Churches in Tri-State to make appeals and raise money for the mission. I have continued to do that for ten years. The site of watching the woman on the roof make mudpies resulted in my writing the title poem in the form of a recipe. Poems about Haiti appear in all three of my books of poems, including two in my recent Chapbook “Eat This Poem.

GER: You have had your poems published in a number of small press magazines/journals and have read your poems to audiences. How important is it for a poet to publish and read their poems in public?

Publishing and reading one’s poetry is a validation and reflection of what the poet wants to say to the world. In publishing and reading the concerns, hopes, and commitments in life can be read and heard. The reading for me is important in continuing the tradition of the Bards in our culture.

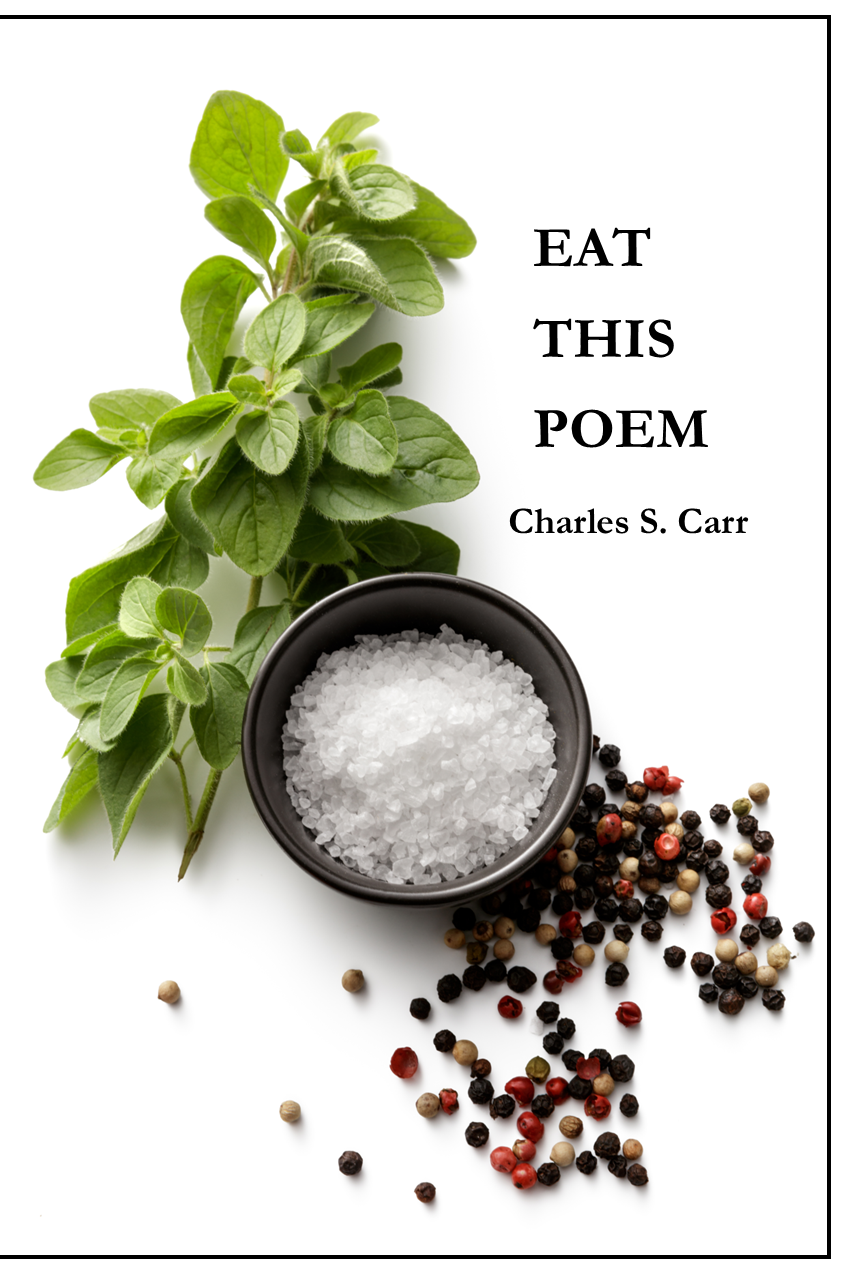

GER: Eat This Poem was recently released by Moonstone Press. Sales from the book will benefit a Ukrainian charity. Tell us about the book and how the benefit came about?

I have had a passion for food and cooking for a long time. I had composed several poems about food- including the relaxation of making soup, a Self Portrait of myself as a salad, and the guilt of a missionary shopping in a Giant’s market in midst of massive malnutrition in Haiti. While I was putting the collection together scenes of the war on Ukraine and the starvation of children affected me greatly. Also I had a long time affection for Ukraine as three of my favorite professors immigrated from Ukraine. I contacted two. al Ukrainian American poets and asked them about organization I could donate the proceeds from the sales of the book. Both recommended Ukraine Trust Chain, a volunteer initiative in Ukraine that was started by Ukrainian Americans living on Philadelphia. To book sales have resulted in $625.00 and I hope to keep working to sell more books.

GER: You have immersed yourself in the poetry scene of Philadelphia as an interviewer, host and writer of poems. How has this impacted your poetry?

Being a poet in this community of truly remarkable poets has provided a life in poetry and friendship with extraordinary people. Reading and listening to other’s work creates opportunities to learn different subjects and a variety of ways to write my poems. Leonard Gontarek has been my mentor and through his workshops and his friendship I come to live a new life in poetry.

GER: How has your non-poetic background come into play in your poems?

For 45 years I served in a wide variety of jobs in helping address wide assortment of needs-employment and training opportunities for underserved groups. Abused and neglected children, helping low-income families access and pay for quality childcare. These experiences let me see a broken City and it has had a lasting impact on how I view the world and the role that poetry can play in speaking to chasm and wrongs of the wider world.

GER: What projects are you currently working on and what can we expect from Charles Carr in the future?

I am putting together a selection of poems from the past 10 years with the goal of submitting for another book of poems.

Books by Charles Carr

Eat This Poem

https://moonstone-arts-center.square.site/product/carr-charles-s-eat-this-poem/454?cs=true&cst=custom

Haitian Mudpies & Other Poems

https://moonstone-arts-center.square.site/product/carr-charles-s-haitian-mudpies-other-poems/22?cs=true&cst=custom

paradise, Pennsylvania

https://www.amazon.com/paradise-pennsylvania-charles-s-carr/dp/0978949935

.

.

Charles Carr of Philadelphia has two published books of poems, paradise,pennsylvania and Haitian Mudpies & Other Poems. Charles has been active in the Philadelphia poetry community for 20 years and he hosted a Moonstone Arts Center Poetry series at Fergie’s Pub for 5 years and is currently the host of a live monthly broadcast Philly Loves Poetry now in its seventh season. Eat This Poem, a Chapbook, published ny Moonstone Press, was released in December. Proceeds of the sales of the chapbook will go to Ukraine Trust Chain.

Charles Carr of Philadelphia has two published books of poems, paradise,pennsylvania and Haitian Mudpies & Other Poems. Charles has been active in the Philadelphia poetry community for 20 years and he hosted a Moonstone Arts Center Poetry series at Fergie’s Pub for 5 years and is currently the host of a live monthly broadcast Philly Loves Poetry now in its seventh season. Eat This Poem, a Chapbook, published ny Moonstone Press, was released in December. Proceeds of the sales of the chapbook will go to Ukraine Trust Chain.

Charles Carr is an integral part of the Philadelphia Poetry Scene. His poetry has been published widely in the small press and three collections of his poetry have been published. He is the host of Philly Loves Poetry on Philly Cam and is active with the Moonstone Arts Center. A native Philadelphian, Carr attended LaSalle and Bryn Mawr Colleges, earning a Masters degree in American History. He has been an advocate for services for abused and neglected children for 35 years. More recently Charles has worked as a volunteer to promote the cause of the poorest of the poor in Haiti. Charles is married. He has one son

Charles Carr is an integral part of the Philadelphia Poetry Scene. His poetry has been published widely in the small press and three collections of his poetry have been published. He is the host of Philly Loves Poetry on Philly Cam and is active with the Moonstone Arts Center. A native Philadelphian, Carr attended LaSalle and Bryn Mawr Colleges, earning a Masters degree in American History. He has been an advocate for services for abused and neglected children for 35 years. More recently Charles has worked as a volunteer to promote the cause of the poorest of the poor in Haiti. Charles is married. He has one son